Splitting off from the spinal cord on either side of the neck, the brachial plexus is a collection of nerves that runs down both arms, allowing for movement and feeling in the shoulder, elbow, wrist, and hand. Tragically, many infants sustain birth injuries involving these crucial nerves during labor or delivery. Some children will go on to live with permanent paralysis and weakness, a condition often referred to as Erb’s palsy.

Brachial plexus injuries are a common form of birth injury, often caused by excessive, and even reckless, pulling on the part of a healthcare professional. In some, but not all, cases, these injuries can lead to life-long consequences.

Minor brachial plexus injuries usually resolve of their own accord, as feeling and control returns to the affected arm over a matter of weeks. Severe injuries, on the other hand, can lead to permanent disability, according to the American Society for Surgery of the Hand. Significant trauma can even rip the nerves from a child’s spinal cord and result in permanent disability.

Newborns often sustain brachial plexus injuries during long and difficult labors. While some of these injuries are unavoidable, many infants are left with paralysis and severe muscular impairments due solely to medical negligence – when obstetricians, nurses and midwives fail to uphold the well-established standards of medical care. In these cases, families may be eligible to file a birth injury lawsuit, pursuing financial compensation and long-term support for their children. Our birth injury attorneys help file these lawsuits.

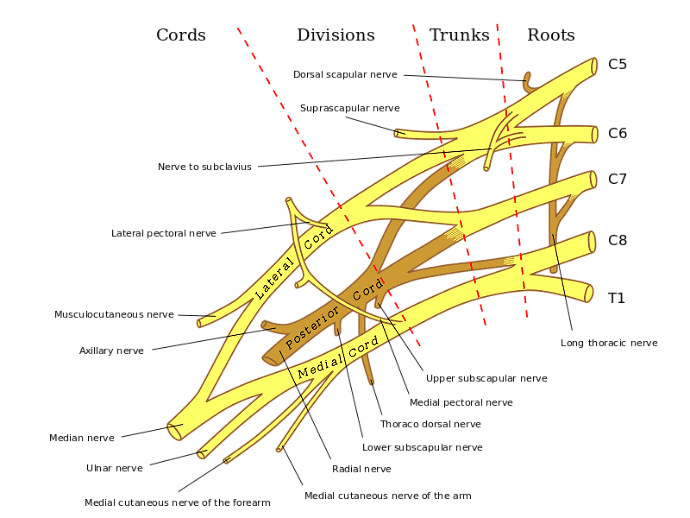

Doctors divide the five nerves that make up the brachial plexus into two rough categories, based on their location. Nerves in the upper brachial plexus originate at vertebrae C5 and C6, higher up the neck. Nerves in the lower brachial plexus, on the other hand, begin at vertebrae C7, C8 and T1, which are closer to the shoulders.

The effects of a brachial plexus injury depend in large part on which portion of the nerve bundle has been harmed. Injuries to the upper brachial plexus, most of which will be classified as Erb’s palsy, are most common. Klumpke’s palsy, an injury that affects only the lower brachial plexus nerves, is extremely rare in newborns.

Nerve damage can be mild, moderate or severe, because nerves can be injured in a number of different ways:

A child’s long-term prognosis, along with the medical treatments required to return control and feeling to the affected arm, will depend entirely on the location and severity of nerve damage.

As we’ve seen, Erb’s palsy is a condition caused by damage to the upper brachial plexus nerves, which normally control movement and sensation from the shoulder to the elbow. How Erb’s palsy will affect a child, however, depends on the severity of nerve damage. The condition’s most common symptoms are usually apparent upon birth:

The Moro reflex is also a key indicator of brachial plexus injury. Healthy infants have a natural way of reacting to being dropped. After losing support, the child will spread their arms outward in one quick motion and then draw the arms inward, like a hug. This is called the Moro reflex. Children who have suffered injuries to the brachial plexus usually display an impaired or entirely absent Moro reflex.

A “crooked” arm, sometimes referred to as “waiter’s tip,” is often cited as the classic sign of Erb’s palsy. The affected arm will hang to the side, rotated inward or toward the back. This presentation, while characteristic, is actually caused by an atrophying of the bicep muscles, not the nerve damage itself.

Erb’s palsy is a birth injury at the intersection of medical complications and obstetric practice. Many women are at risk for long, difficult deliveries – but in most cases, it takes medical intervention, often manual force, to injure a child’s brachial plexus. Serious negligence can creep in at any moment.

It’s difficult, however, to predict which children will suffer brachial plexus injuries. Anticipating a difficult delivery is easier. Here are seven health complications that can increase the risk for a long labor and delivery:

Faced by these risk factors, some obstetricians will choose to order an emergency c-section, rather than risk the possibility of further complications by continuing on with vaginal delivery. Some risk factors are so critical that an emergency c-section becomes medically necessary. When a c-section is indicated, failing to order the procedure can be a negligent omission.

Shoulder dystocia likely presents the highest risk of brachial plexus injuries. This complication of delivery, a true medical emergency, occurs when a child’s head passes through the birth canal but shoulders remain lodged behind the mother’s pelvic bone. Without immediate medical intervention, infants can quickly suffer oxygen deprivation, a common cause of severe brain injuries. To alleviate the situation, many obstetricians apply physical force, pulling downward on a child’s delicate head in an attempt to draw the body further through the birth canal.

The risk for severe injuries, including harm to the brachial plexus, should be clear. Medical intervention must be both prompt and careful. In fact, medical professionals have a legal obligation to prevent harm whenever possible. Without using extreme care, a doctor can easily injure a child during the first moments of life – injuries that may well have life-long consequences.

Even with rigorous training, obstetricians continue to harm children at alarming rates. Shoulder dystocia remains the leading cause of brachial plexus injuries. Children who become stuck in the birth canal are over 100 times more likely to sustain an injury to the brachial plexus, according to researchers at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital.

The use of assistive devices should also be cause for concern.

Due to their inherent risk of injury, forceps and vacuum extractors have become less popular over recent decades. Many obstetricians, especially inexperienced specialists, refuse to use these tools at all, opting instead for emergency cesarean sections when a labor becomes protracted. But birth-assistive tools are still in common use – and raise the risk of severe brachial plexus injuries by an extraordinary degree.

In one recent study, Israeli researchers found that nearly 25% of children with Erb’s palsy had been delivered via forceps or vacuum extraction. Only 5% of the children born during the study period had been delivered using birth-assistive instruments.

Erb’s palsy is not necessarily a permanent disorder. Again, it all depends on the severity of nerve damage. After minor injuries, the nerves can heal. Physical therapy may be required, along with home exercises and gentle massage, but there is little risk of long-term impairment.

More severe injuries, on the other hand, may require surgical operations. Nerve grafts, nerve transfers and muscle transfer operations can help children regain arm function, the Mayo Clinic reports. Surgeons usually wait before recommending an invasive procedure, especially where infants are concerned. Three months is a typical wait-time, as doctors watch closely to see if the injured nerves can heal on their own.

There are children, however, who will never fully recover function and sensation in the affected arm. Brachial plexus injuries impair not only a child’s ability to move and feel, but also their ability to develop physically. Muscle development and circulation can be inhibited and, as children age, their initial birth injury can lead to significant complications.

Continue reading: